A decade without my dad has passed. And time keeps on moving. February 15, 2024 will mark eleven years since Ken Henshaw died from a terminal brain tumor.

I was seventeen when my dad died, and I had no idea how to express my grief.

At first, I clung to family as our family’s first grandkid was born seven days after my dad died, which gave us a much needed distraction. We rallied together to take care of our new baby and new parents. The celebration of new life was easier to talk about than the mourning of our dad’s death.

In those early days, I also held tightly to perfection. I didn’t miss school, turned in my assignments on time even when teachers offered extended deadlines. I was proud to not accept help. I ran for class Vice President and won, I wrote the script of school’s play and performed in it, and I founded a new club at school called OAK (Outdoor Adventure Klub).

It didn’t stop there. I was voted captain of both the cross country and track team. I ran faster than I had ever run before, making varsity and winning states. I pushed myself, and finally ran a sub five minute mile (4 minutes and 58 seconds). Running was a healthy way for me to release emotion and hugely effective in helping me process grief, but at that time I wasn’t aware of it.

I remember being praised often during that first year. Members of the community praised me for this hyper vigilant success. “You’re handling this so well,” and “You are so mature for your age,” were common things I heard. I thought I was doing so well because I didn’t cry in school, I didn’t melt down at practice, I didn’t express any of the emotions I was feeling.

And then college happened.

Without my dad, I felt incapable of making a decision of which school to go to. He was so passionate about college, and was particularly attached to us getting “a good Virginia education.”

I was frozen with indecision for a long time, and there was this desire bubbling up in me to flee. Instead of college, I dreamed of being an au pair in New Zealand and then work on a cacao farm in Hawaii. But my mom told me to go to school, so I did. What choice did I have? She had the money.

If I couldn’t leave the country, I still wanted to be as far away from my community as possible. I didn’t want to walk down the street and be known as “a Henshaw” or “Ken Henshaw’s daughter, that poor girl.” It was too painful to be recognized.

My mom just shrugged at my dad’s “Virginia only” rule, and let me go to the mountains in North Carolina. Five hours did the trick: I went to a college where my name meant nothing. At first, I didn’t tell anyone that my dad died. I could hide from that fact and build a new reputation for myself.

I quickly realized that I didn’t have a clue what I was doing there. It sounded a lot better on paper to not know anyone, but it was the first time in my life that I didn’t already belong to a community. It was lonely and I was lost.

Signing up for classes felt like a game of whack a mole- it was a no to computer labs and vague topics under the umbrella of the “Business School.” It was a no to anything related to science and math, but the problem was finding what I wanted to do.

My whole life I grew up dreaming with my dad of becoming an author and a teacher. It was perhaps the career path he projected on to me, but I agreed that it was a great fit. I loved school and writing so it seemed like an obvious choice.

After he died, it lost it’s appeal.

I was lucky to grow up with a dreamer of a dad.

He quite literally had the word “DREAM” in big wooden letters sitting on top of his desk. As a young kid, he allowed whimsical dreams to seem real. The two of us conjured up the idea of building secret passageways in our house that required kicking the right floorboard or pulling a candlestick that would lead to a quiet library with floor to ceiling bookshelves, a plush chair and a bean bag.

Long drives with my dad were for dreaming out loud.

He never stopped asking me what my dreams were as I grew older. He started asking more logistical questions that included the how, what, when, where and for who, helping me understand the necessary steps I needed to take to achieve my dreams. I grew up believing that I could do anything I wanted if I worked hard enough.

My first dream as a kid was to write books.

Bedtime stories was an important part of my childhood, but it wasn’t books that were read out loud. My dad made up an entire series of bedtime stories about Pete the Dragon, a friendly dragon who lived in the woods behind the baseball field. Pete the Dragon would play in all the kid’s baseball games, with each story having an underlying moral lesson of playing fair, being nice to each other, and having fun whether you win or lose.

At some point my dad stopped telling Pete the Dragon stories and instead asked me to tell him a bedtime story. Excited that someone wanted to listen my rambling, I launched into intricate and imaginative stories that sometimes needed multiple nights in a row to finish because I would literally talk myself to sleep.

Oral story telling was my forte until I learned how to write. I talked to myself in the mirror, inventing characters with long back stories that I would become every time I went to the bathroom. I played dollhouse every day for hours on end, never letting anyone else play because they didn’t understand the years worth of social dynamics between the dolls that I invented.

My dad spent many mornings at the breakfast table listening to me recount every dream I woke up remembering. I described every whimsical detail in between bites of cereal. Each dream was complete with universal messages of friendship and the importance of including other unicorns. He would listen intently until the very end of my rambles, then he’d slap his hand on the table and exclaim, “What a story!”

Once I learned to write, he still listened to my dreams at the breakfast table. But when I was done, he would hand me a yellow legal pad notebook and tell me, “Write that one down, that could be a book one day!”

I became accustomed to unwrapping a journal and a new book for each birthday and Christmas present from him. I remember one day he picked me up from school and asked what was going to happen next in my vampire romance story. I launched into my ideas about Jenny turning John into a vampire out of true love (a blatant rip off of my favorite story at the time…Twilight), before I realized that he snuck into my room while I was at school and read my diary!

My anger never lasted though, because he always wanted to sit and listen to whatever story I had written.

I grew up believing that it was only a matter of time until I published a book.

By the time I got to college, I didn’t even consider the possibility of majoring in writing. The dream just wasn’t there anymore. Outdoor Education seemed like the easiest major to me. My classes included kayaking, canoeing, backpacking, and rock climbing- all things I had never done before, or maybe tried once at my country cousin’s house in rural Virginia.

I didn’t write anything for three years after my dad died.

Grief was real messy for me as I navigated the already awkward growing up and leaving home stage of life. Instead of learning how to express grief and move through it, I spent my college years chasing the highs of life, wanting to only feel happy.

I avoided all the hard grief feelings, telling myself silly things like “Be happy that you’re alive,” and “You’re gonna die so you might as well live it up.”

But chasing highs goes hand in hand with running away. I avoided going home, I didn’t call my family as much even though I missed them, and I certainly didn’t tell them the full extent of what I was up to. Debauchery and dancing five nights a week, skipping class to watch the sunset over the Blue Ridge Mountains every day, and numbing with the so heavily advertised “pleasures of life” (alcohol, drugs, sex and travel).

I was twenty years old when I went on my first backpacking trip with my class. I was a fish out of water, freezing cold and scared to wake up and see snow out of my tent. But I loved the struggle, which was easier to navigate than my own internal world of feelings.

Everything shifted after that backpacking trip, which had three important effects:

- It was the longest stint of days that I remained sober (a week). This was the start of chasing a new high: living outside.

- We completed a solo experience in the woods, and to my surprise, I cried the whole time. I laid underneath an oak tree, looking up at the sky through the branches, and I talked out loud to my dad for the first time since he died. I let out year’s worth of suppressed emotion and left that solo spot feeling better than I had in years. A very important seed was planted: the wilderness is a healing environment.

- And lastly, I pulled out my journal and wrote about the experience. It was the first time I wrote anything aside from school work in three years.

The next semester I signed up for a creative writing class, where we were instructed to write a short story. In my fabulous fashion, I waited until the night before my short story was due to start. I sat down at the computer ready to write a fictional and futuristic world where there was only a few real humans left. Everyone was technological altered with the perfect smile, synthetic eyes, and robotic limb replacements. Instead of writing this world that I created, I sat down and sobbed for nearly nine hours straight.

I wrote the entire story of my dad getting cancer and dying in one night.

When I turned in the short story, my class gave feedback:

- “Is this a chapter in a book?”

- “This could be a book.”

- “I want to read more, please make this a book.”

“No, it’s just a short story,” I said with a flat voice, waving them off.

I felt like an outsider in that writing class. I quite literally looked different than everyone. I was the hippie in a drug rug, stoned and staring off into space among a sea of overly correct hipsters wearing reading glasses with patches on their jackets who were publishing their own zines on the side. The hipsters gave feedback about elaborate literary tools I used in my writing that I didn’t even know existed.

I didn’t see myself as a legitimate writer. But I signed up for another creative writing class, and another, and finished college with several short stories. But writing felt like my little secret.

My whole life was expertly segmented into three groups: my family and friends from home, my party friends, and my outdoor people. None knew much about the other. I wasn’t ready to share my passion for writing with the world. I was held back by the fear: what might people think??

I was twenty one and becoming tired of my own life hiding from grief, chasing parties, and keeping my literary side quiet. My dad didn’t raise us to care what people thought, he raised a bunch of damn free thinkers.

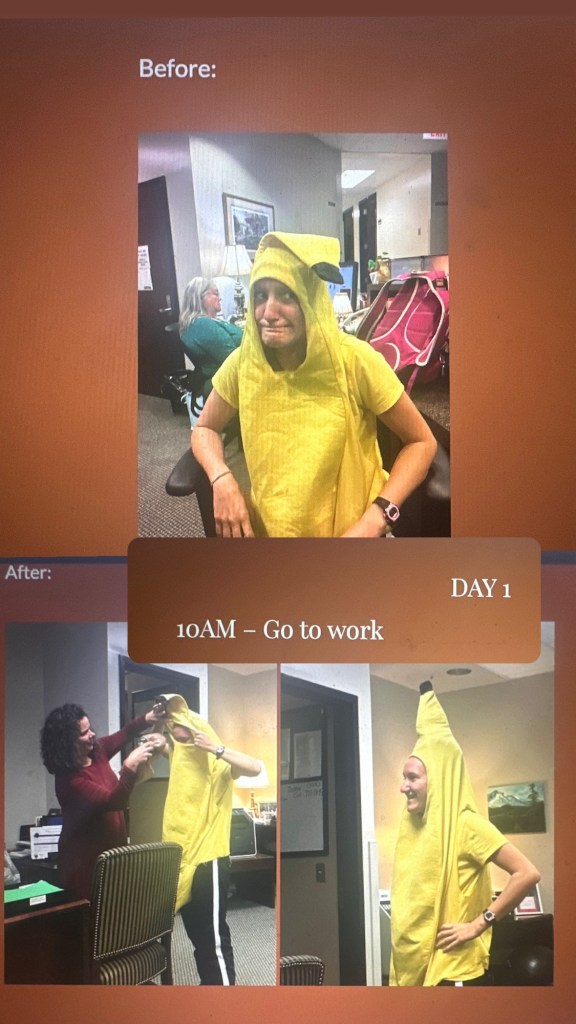

So in my last semester of college, I decided to wear a banana suit every day for seven days and write about the experience. I started my first blog, The Banana Blog, which was about overcoming fear of what other people thought.

(The Banana Blog is no longer public on the internet but may make a comeback…) Here’s a sneak peak:

The banana suit was a representation of not giving a fuck, but truth be told…I still gave way too many fucks. After the week of posting daily, I got a lot of feedback and excitement to keep posting. It wasn’t until I was twenty two that I revisited the site and continued posting, but by the time I was twenty three, I let the blog peter out.

After I graduated college, I drove across the country five times, still carrying my unprocessed grief with me. I had that flight instinct for years, wanting to be anywhere but here, because the mountains are bigger out west.

Over time, the beauty of the natural world cracked me open. It was the mountains and rivers that brought me back. In the woods, I could talk freely to my dad. I updated him on how the whole family was doing, laughed with him about my silly mistakes, and cried with him when he wasn’t around to celebrate milestones. The woods became my safe haven.

Spending weeks with people in the backcountry opened me up to a life that really felt worth living, far more fun and engaging than the all nighters spent dancing. Living in the backcountry also made my heart ache for family and for things that felt familiar.

Grief can be a connector or an isolator.

For many year, I chose to isolate myself in the mountains of North Carolina, then again on the road to California. Every time I drove west, I kept telling myself that I was never coming home! But I never did last a full year before turning around to drive back east to spend a few months with my family. As much as I wanted to hide, it felt better to be in the company of my mom and siblings.

I learned this the hard way: avoiding grief only makes it stretch on longer. Running away feels temporarily better. Numbing with alcohol and drugs makes everything more fun for a moment, then way harder. Sitting in the woods with tears streaking down my face, talking out loud to my dad and collapsing in the leaves from sheer exhaustion feels a little shitty in the moment, but infinitely better in the long run.

Backpacking brought me back to writing. I started carrying a journal with me on trips, sporadically scrawling notes about the beautiful places I found across the country with a dose of feelings scribbled next to descriptions of trees.

On the the sixth year anniversary of my dad dying, I was twenty four years old on a winter backpacking trip with my friend Cary in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

I remember waking up to a snow storm that melted by midday. We hiked through the night without headlamps under the moonlight and at the end of the day I confessed, “Today is the death anniversary of my dad. And I’m confused, because I’m supposed to be sad today. But I’ve been having a blast!”

Cary looked at me and said something that changed my life forever: “Well, maybe it’s time to stop mourning the death, and start celebrating the life.”

It shook me. I realized that every time I pictured my dad, I pictured him sick and dying. Hard memories of the last moments. I had to rack my brain for the regular memories, the ones that made up the rest of my life.

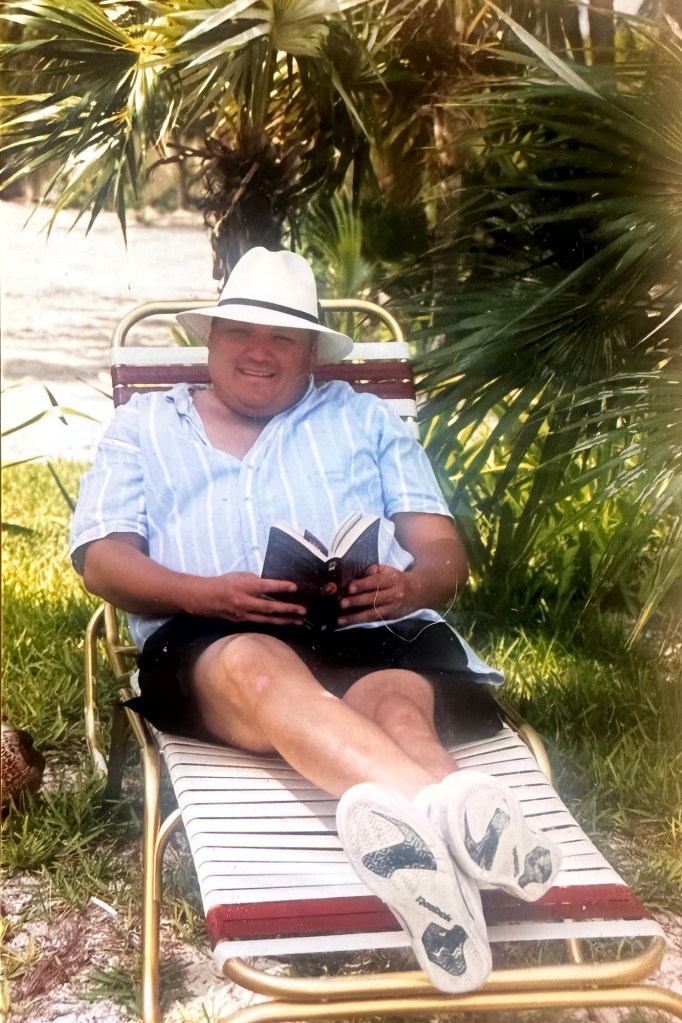

When I did this, I could see my dad in two settings: standing at third base giving me a secret signal, and sitting quietly on the beach with a book. He was simultaneously a lively and introspective dad. He coached me and my three siblings in baseball/softball for over twenty years, and became quite famous in our community for his pranks.

After a hot summer softball practice, he would gather the team around in a circle and tell us that we were going to attack the other team’s practice. He would arm us with coolers of water balloons and tell us to fill up water guns at the spigot. We would run, giggling, onto the baseball field, attacking our rival teams with water balloons. Every surprise attack ended with eating juicy watermelon together, effectively eliminating the idea of anyone being our “rivals.”

Being the coach’s daughter, I got to fill the water balloons at home and knew about the prank before it happened. I also overheard my dad calling the other team’s coach to plan out the “surprise” attack, always clearing it with them beforehand. I remember being frustrated with him and telling him, “Dad, that ruins the surprise!”

He wouldn’t explain anything, he’d just smile and say, “You’re missing the point.”

Other notable pranks include short sheeting all the parent’s beds on travel tournament weekends. My dad would host a “parents only” meeting in the hotel lobby so the coast was clear for the kids to go from room to room, perfectly folding the bedsheet in half and remaking the bed, so when our parents tried getting in their feet would get caught. He taught me how to short sheet a bed and trusted me to teach the rest of my teammates. A harmless prank that made kids laugh at their parents.

One of his more controversial pranks involved toilet paper, “teepeeing” the houses of rival team’s coaches. He would even have us kids spread dog food in the front yard so that every dog in the neighborhood wanted to sniff and eat their grass. The best part of the prank was coming back the next day, laughing with the victim, watching their reaction, then helping them clean up the whole mess. The lesson of pranking was not to piss people off, but to bring people together through laughter.

As the coach’s daughter, I was a switch hitter. I helped my dad with pranks but I also helped anyone who was interested in pranking my dad. The moms got together one summer during a travel tournament with an idea of how to prank my dad back. All the girls on my team were in on it, and we couldn’t stop giggling as went through his suitcase and replaced all of his underwear with thongs while he was in the shower.

We squealed in delight and ran down to the lobby, showing up early for the player’s meeting. My dad came down to the meeting making a big show of picking wedgies. We laughed and laughed and laughed as he pranked us back, pretending to wear the thongs and complaining loudly that “he was having a bad laundry day.”

Below is an incredibly blurry photo of my younger brother’s baseball team pranking my dad by attacking him with shaving cream! It was tradition to prank him back. Look at his face, he loved it.

For the first few years after my dad died, I drove home every February to be with my mom and siblings. We didn’t sob or profess our feelings through poetry, we put our heads together giggling and committed low level crimes.

To honor our dad, we got together with ideas of who to prank and how to do it. Our targets were old targets, our dad’s friends from the early days of coaching and pranking. We filled cars to the brim with balloons and stole yard signs from around town, putting them all in one person’s front yard. I don’t know exactly when or why we stopped doing pranks, but it became harder each year to get us all in one place at the same time.

The booming sound of my dad’s laughter during a successful prank is equally present in my memory as the image of him silently reading a book for hours.

I can still see him sitting underneath a rainbow umbrella with his feet in the sand and a book in hand. For just one week at the beach, he packed five to ten books and sometimes finished all of them. Then he’d take me on a drive down to the island’s only book store, and pick up some more. He’d buy whichever books were historically relevant to the island and I picked out pirate stories to read.

My dad loved reading about history. He had a particular obsession with Thomas Jefferson and the other founding fathers. He once read a ten book series detailing every battle in the Civil War, and several of those books had one thousand pages, all the while listening to the waves lap against the eastern shore.

When we were teenagers, my mom took us on hikes in the Blue Ridge mountains: thrilling adventures to find waterfalls, swimming holes and view points. My dad always opted out, dropping us off at the trailhead and plopping himself in a chair at an overlook with a book. As a kid, I couldn’t fathom why he would want to sit in one place for so long, reading instead of adventuring. But he valued his solitude and preferred the adventure of the mind.

I was the only kid who took to reading like my dad. I devoured the Harry Potter books, then the Percy Jackson series and the Twilight saga, continuing on to read Eragon and any fantastical fictional world I could get my hands on. After a while my dad started pestering me about the books I read. The trashy girl drama novels of middle school drove him crazy, and he stopped paying for them.

“When are you going to read something of substance?” he complained, watching me pick out yet another love story between mythical creatures.

Defensive, I told him that I would read whatever I wanted and I would pay them for myself because I was old enough to babysit and to butt out of my life! He just laughed, because was never good at butting out. He was the parent who knocked on my door repeatedly until I opened it, just to say, “Hey, what are you doing?”

Around the same time that my dad was diagnosed with cancer, I started reading books by Mitch Albom. I sat by my dad’s hospital bed discussing “The Five People You Meet In Heaven,” a book of substance that my dad approved of. I read parts aloud to him, but by the time I left for school and came back, he had already finished it.

“Do you think this is really what happens when you die?” he asked. “Do you think you really meet those five people?”

I thought for a while before I answered. “No,” I shook my head finally. “I don’t think he’s saying ‘this is what happens when you die.’ I think it’s more of a story for people who are alive and are worried about all their regrets in life. I think the book is about looking back and seeing how it was all important.”

I remember the look my dad gave me when I said this. He stared at me for a long time without saying anything. So long that I had to ask, “Dad? Did you hear me?”

He chuckled and nodded, lost in thought.

“Do you think that’s what happens when you go to heaven?” I asked.

“I’m not sure,” he said. “No one knows for sure.”

“Yeah, no one knows,” I agreed. I think he fell asleep in the middle of our conversation, or perhaps I just walked away. At the time I didn’t think my dad was dying, I thought he was getting better. As the years have passed, I wonder about that conservation more and more. I wonder what my dad thought was going to happen when he died.

I spent a lot of time sitting next to my dad as he laid in bed, sick with cancer. He had an idea to write a children’s book about Henry Box Brown, a man who escaped slavery by mailing himself in a box to the North for freedom. My dad instructed me to write the story because his right hand shook too much for him to write anymore. I remember sitting with him, happily sketching out the book, dreaming until the day he died.

I don’t remember where I put those pages.

It took me a long time to learn how to celebrate the life of my dad.

When I had that backpacking revelation on the sixth year of wanting to celebrate his life, I spent the next few years wondering how best to do that. It wasn’t until I went to Mexico and saw the Day of the Dead celebration that it really sank in. The streets were bursting with altars of loved ones, pictures with marigolds and picnics in the graveyards.

I watched from the sidelines as people approached altars and left the dead person’s favorite drink, candy, or cigarette. I saw people laughing and chatting with the spirit of their loved one, standing at the altar as if they were smoking with their late friend. I learned a lot watching those people continue their relationship with spirit.

I wanted to do the same thing, but it took another few years to put this learning into practice. Once again, I fell into the trap of becoming obsessed with perfection. How do I celebrate my dad in the BEST way? The most intentional, profound way? The pressure I put on myself made me freeze, and February 15 would pass without me doing anything, for fear of doing the wrong thing. Then I kicked myself for doing nothing, and no body’s ever motivated from a place of shame.

This cycle exhausted me, and at some point I tossed away the idea of crafting the most perfect celebration. I figured, just do something.

Literally doing anything is better than doing nothing. So over the last few years, I have tried on some different things with varying degrees of thoughtfulness. I’ve lit fires and shared stories about my dad with friends. I’ve lit candles and sat with pine cones and read poetry. I’ve written letters to my dad and flown home to spend quality time with my family.

Eleven years have passed and I’ve collected enough books to start my own little home library. I live in a house with wooden bookshelves that are built into the wall, and the journals I’ve filled with thoughts throughout my life take up an entire shelf.

I think of my dad when I sit down to write.

The excitement in his voice when he said, “That could be a book!” still plays over and over again in my head.

To celebrate my dad this February, I’ll put out some photos of him and sing along to “Piano Man” by Billy Joel. I’ll cook a meal as he always did for us, and I’ll make a point to sit down and read a book of substance. I’ll write a book of substance too. Maybe I’ll sit outside an at overlook and write a letter to him, sometimes I do that. I probably won’t play baseball or shoot any hoops.

And on the actual day of February 15th, I’ll be in the car driving, which is something my dad did a lot of. I’ll be on my way to a writing workshop in Zion National Park. I’ll spend the weekend thinking of him as I workshop the first chapter of my book with a long time idol of mine: Craig Childs. I can’t think of a better way to celebrate my dad than to spend the whole weekend writing.

I love you, Dad!

I miss you, Dad.

We’re thinking of you, Dad.

And Dad, I’m writing a damn book!!!!!!!

Like REading this Blog?

Consider Making a one Time Donation!

Become a monthly donor and RecEive exclusive member only content

Platinum status! Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Thank you!

Thank you!

Thank you!

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly

<

div dir=”ltr”>I loved reading this!!! Love you!!! Unc

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beth, this brought tears to my eyes. You have such a gift; I felt as though I was walking through life with you and your dad while reading this essay. Sending peace to carry you through the week… May your father’s memory always be a blessing.

Katie

http://www.kaitlynbean.com 616.914.2061

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank so much for reading and for these kind words, Katie! I’m checking out your website now 🙂

LikeLike

I seem to always be waiting in the back room of a store, waiting to check in, as I read your posts. I find myself sobbing and sharing stories with almost complete strangers. Love you so incredibly much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I find myself doing a similar thing…waiting to see if you read, reading your comment and tearing up too. Love you so much Sara!! Thanks for all the support!

LikeLike

Beth – I’m so very sorry that you lost your Father. I know the feeling well. I lost my Mother 20 yrs. ago to Spinal Cancer. She taught me so much! My real Father didn’t want me after I was born.

LikeLike

Your clarity simple, your depth complex.

Hi Beth, when I was young in the early 70s an older sibling had a plastic toy named the View-Master. I remember it’s color being cerulean blue but that could have been an association with big sky landscapes waiting inside. Cardboard disks came in the box, each round laced with picture slides and anticipation . When pressing ones face against the View-Master hard, eager eyes of any age can bear indentations. Something about going inward, needing long hard looks, regardless. It’s the work and your meaningful writing work offers healing plus more. Wishing you expansive mountain ranges, panoramic views of all four directions. Thank you Beth for sharing it’s been a gift to meet a Dad I wished to have had.

ISM, RI.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for taking the time to read and write this thoughtful response! It brought a smile to my face.

LikeLike