When my older brother Andrew bought a house, he woke up to a repetitive thud, thud, thud coming from the foyer. It was Dad, hammering a nail into the wall, but not even with a hammer. A rock from the yard. He was not hammering but rocking a nail into the wall.

“What the hell are you doing?” Andrew asked.

Dad looked at him like showing up unannounced while Andrew was sleeping was normal. He tone remained very serious when he said, “Every home should have the Declaration of Independence hung on the wall,” as if that were the most obvious thing in the world.

He lifted a lavish framed copy of the Declaration of Independence and hung it on the wall. Pleased with his work, he left.

Seventeen years later, it still hangs in my brother’s house, though on a different wall and is not the first thing you see when you walk in the front door.

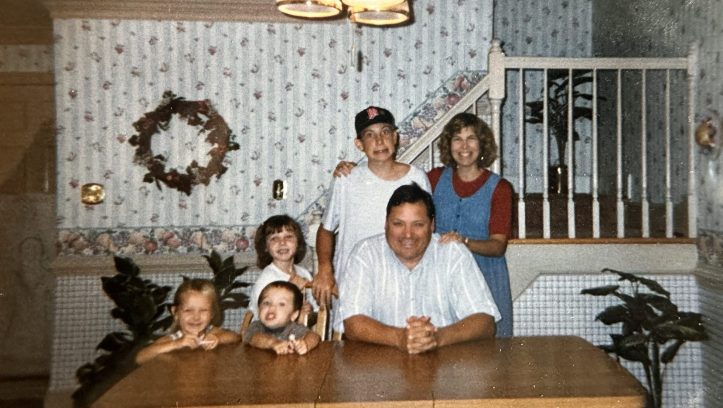

It’s been thirteen years since our dad died of brain cancer. Thirteen years since the tumor took over our lives, living room, and porch. Thirteen years since my uncle built a wheelchair accessible ramp into the driveway.

Dad’s framed copy of the Declaration of Independence hung in his office at home, a doorless room off the foyer, where two leather chairs faced his desk. I’d sit there, watching him peer at documents with his reading glasses on the tip of his nose.

I always admired how John Hancock signed his name the biggest. How bold! I thought.

“The Declaration of Independence says that all men are created equal, do you think that was true at the time?” he’d ask if he saw me looking at it.

“No, because a lot of men were slaves,” I said, to which he nodded. “What about the girls?”

“What about them?” he asked.

“Why doesn’t it say all men and women are created equal?” I asked.

“Why indeed.”

I’d roll my eyes at his non-answer, but this was typical. He often answered questions with more questions.

Thirteen long years without my dad, not only quizzing me on United States history but exploring the ethics of it all too. Thirteen years since a moving vehicle suddenly swerved off the road to read a historical sign about a bloody battle from the Civil War in the middle of an overgrown, tick infested field.

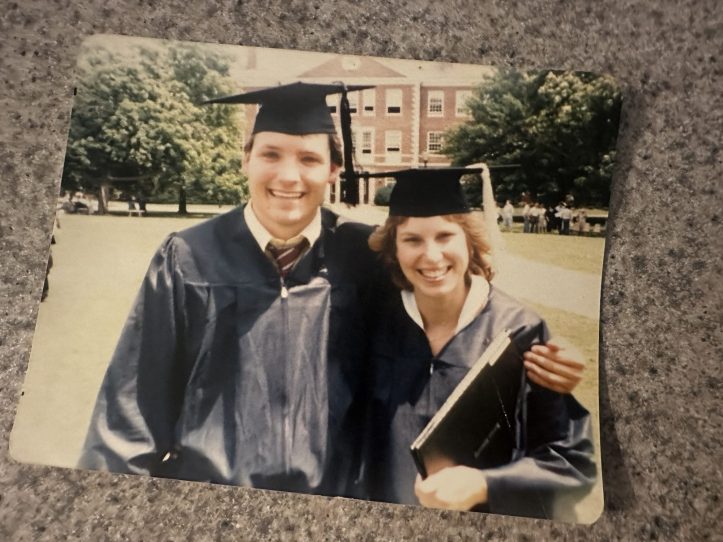

My parents started dating in high school. For my mom’s 18th birthday, my dad’s “present” was taking her to the courthouse so she could register to vote because it was her right as an American citizen and she ought to exercise to it. Thoughtful? Sure. Romantic? No.

When I was in fourth grade, I auditioned for the role of Molly Pitcher in the school play. She was a Revolutionary War hero, bringing water to wounded soldiers on the battlefield, and even did her part shooting a cannon at the Battle of Monmouth when her husband was injured. Badass!

For the play, I wore a bonnet and a simple 17th century dress. Mom sewed on an apron. Dad was proud. I didn’t get the part though.

The play was a musical and the audition involved singing Happy Birthday. I gave it my all. From the look on my music teacher’s face, I didn’t nail it.

Instead, they gave me a speaking role that didn’t even exist before I tried out. So instead of being the great Molly Pitcher, I introduced her.

It was all for the best, I wasn’t as ready for the stage as I thought. When I stood in front of the microphone, my voice softened to a mere whisper, my eyes bulged, and I almost didn’t say anything at all. I froze, and the girl who got to sing Molly Pitcher’s lines crushed it. The crowd even gave her a standing ovation.

Later that night, I wrote in my fuzzy purple diary a list of my enemies: her and my music teacher.

Thirteen years have passed without my dad and over twenty years since anyone has gifted me a framed photo of Thomas Jefferson for Christmas.

I remember my third visit to Mount Vernon, George Washington’s home. I was eight or so, and my hand shot up to answer the tour guide’s questions.

How many years did the revolutionary war last? Eight, obviously.

What was the first major battle? Battle of Lexington and Concord, duh.

I could tell Dad was proud when I did this. My siblings rolled their eyes and stared off into space. I remember feeling torn about who I wanted to impress, them or my dad, so I went back and forth between saying history is stupid, who cares? and reading every plaque we passed.

That year, George Washington’s mansion had recently been restored, and the restoration guy was the tour guide. He made jokes about how hard it was to restore a drunk man’s work from the 1700’s. The fireplace he restored gave him a hard time because the bricks were historically laid sideways and crooked. The crowd chuckled and moved on to the next room.

“Dad, what’s drunk?” I whispered.

He tried pretending he didn’t hear me, so I asked again.

“Something stupid,” he finally said as we moved on to view the Yellow Room, a fancy bedroom with yellow walls, yellow pillows, and yellow curtains around a bedpost with pillars.

The tour guide led us out into the gardens to the slave quarters, noticeably more rundown, just a single roomed log cabin. After the tour, Dad would press us with questions while we ate peanut butter jelly sandwiches at a picnic table.

“Do you think George Washington was a man with good morals?”

“I don’t know,” I’d shrug.

“As a boy, he inherited eleven slaves. What would you do if you inherited slaves?” he’d ask.

“I’d free them!” I said on my high horse.

“Excellent, and how would you manage your father’s 280 acre farm that was passed down to you at eleven years old?” he asked.

“Well, I could pay the slaves, they could be employees instead.”

“With what money?”

“I don’t know!” I’d say, getting frustrated. Grappling with our country’s dark history at the age of eight was less fun than watching episodes of Lizzie McGuire, but it was important to my dad.

He’d continue to recite historical events, like how George Washington wrote in his will that he wanted his slaves emancipated once his dear wife, Martha, died.

“So, did George Washington have a change of heart?” Dad asked.

“Kind of…” I said. “He definitely felt guilty, like he knew slavery was wrong. But he didn’t free them when he was alive because he didn’t want to work in the fields.”

“That’s right. Did he take a stance on slavery while he was President?”

“No.”

“Which President did?”

“Abraham Lincoln.”

“That’s right.”

“I love Abraham Lincoln,” I sighed. At some point in my childhood, I adopted a very weird crush on him and wrote very embarrassing things in my diary like Abe is my babe with hearts drawn around it. I don’t always tell people this. I guess I’m feeling sentimental, reflecting on life with my dad which felt so normal but now seems so fleeting.

Seventeen years with Dad feels too short.

I didn’t always love historic visits, I was still a somewhat normal kid, if you can believe it. Dad was known for turning a three hour drive into an eight hour drive by stopping at historical sites on the way without telling anyone that was his plan all along.

One summer on the way to the Outer Banks for a family beach vacation, a too early turn signal sounded the alarm.

“This isn’t the beach,” one sibling would say, pausing the CD on their walkman.

“Uh-oh.”

“Dad!”

“Where are we going?”

He’d turn around in the front seat with a smile and say, “I got us all tickets to the Wright Brother’s Memorial.”

“Not again!”

“Who cares about aviation!”

“We want to swim in the ocean!”

He didn’t care. We were going to honor the first twelve second flight. We were, at times, held hostage to our nation’s history.

My siblings and I grew up in a house with a robust costume box, with sequined shirts and pirate hooks exploding out the side. I don’t remember exactly why the box had four “Founding Fathers” wigs, the white ones aristocrats wore with curls on the side and a ponytail out the back, but they were a staple of playing dress up.

If you’ve ever sat in a waiting room for a chemotherapy appointment, you know how depressing those rooms can be. Dad wanted to lighten the mood for everyone, so when Mom rolled Dad’s wheelchair in the office for his first appointment, he was wearing that Thomas Jefferson wig.

He kept saying things like, “I hope I don’t lose all my hair. I really love my hair,” while twirling the strand by his ear. Strangers didn’t quite know what to make of him. Side glances were cast while others stared openly at what they probably assumed was a crazy person.

He was wheeled into a room for chemo, and on his way out he hid the wig in his wheelchair. When the door opened, he yelled, “Damn it! They got it all! All my hair on the first round!”

The bleak waiting room erupted with laughter. The nurses, patients, caregivers, receptionists, everyone smiled. He leaned into his sense of humor more and more as he neared death.

I told that story at his funeral in front of hundreds of people. The room was so packed, people were sitting in the aisle and standing in rows in the back and out the double doors.

Before the service, I hid the wig under the podium and pulled it out during my speech. I remember the sound of the room echoing with laughter steading my shaking hands.

I’ve spent every one of the past thirteen years wishing he was here. Wishing he could’ve met his grandkids, helped me pick out a college, helped mom figure out what to do when all us kids were smoking pot down by the river with our friends. I wish I could call him and ask what the hell is going on with the politicians.

I miss Dad most during transitions, like moving across the country, graduating college, or getting a new job. Moments that are happy are sometimes dulled by the fact that he isn’t there to see it all.

It took about six years to transition from mourning his death to celebrating his life. The memories of his cancer ridden body faded and the ones of him belting Billy Joel’s “Piano Man” out the car window returned.

Acceptance is inevitable. It happens at different times in different ways for different people, but eventually we all have to learn to live without loved ones. Acceptance is less of a choice than I thought, and more just a fact of life.

I see how his death threw me into the life I have now, a life I love and am proud of, which is not to say that I’m grateful things happened the way they did. Though it’s important to acknowledge that the shit life events thrust us into becoming another version of ourselves.

Grief motivated me to leave Virginia at eighteen. I didn’t want anyone stopping me in the grocery store to talk about how they too missed Kenny Henshaw. I sought anonymity and found it driving across the country back and forth. I wonder if I would’ve fallen in love with the West and moved to the red rock desert had my dad’s brain not been taken over by a tumor.

Acceptance is inevitable but feeling connected to ones we’ve lost long after they’re gone is not as natural. That’s something I had to work for.

It took me five years to realize I could still talk to my dad. With my back against an oak tree in Pisgah National Forest, I updated him on my life, what books I was reading, what sibling was pissing Mom off most and what the grandkids were like. I don’t have the slightest clue if spirits can hear us but I believe they can. My guess is they like hearing from us.

Dad never saw the red rock desert I live in. He hated airplanes and wasn’t going to pay money to be terrified, so vacations growing up remained within driving distance on the East Coast. He never walked through a canyon, never stumbled upon an ancient dwelling with pottery shards and arrowheads littered at his feet.

It took less than five minutes after his death for someone to say, “He’ll always be with you,” but five years to grapple with what the hell that meant.

Hearing that as a teenager I just thought, “Shut up. He’s gone.”

Because when you’re seventeen being with you meant in the physical form, in the flesh, able to talk back and answer questions, not that answering questions was his speciality. Spiritually with you wasn’t good enough.

There came a time, maybe seven years later, when it did become good enough, because the alternative is feeling disconnected forever.

Thirteen years later, grief is less consuming than it once was. I find myself feeling irritable each fall, the time of year Dad was diagnosed with cancer. I notice an underlying frustration in February, the month he died. It’s little moments of reprimanding my toaster when it burns a bagel that remind me the grief is still there.

My early years were spent listening to Dad’s bedtime stories of Pete the Dragon, a nice dragon who lived in the woods and loved to play baseball with the neighborhood kids.

I was and still am a firm believer in magic. So yes, I like to interpret a well timed sun beam hitting my face when I think of Dad as a sign from him.

The other day, a hawk sat prominently on a rock watching me and the dogs on our normal morning walk. The hawk stared straight at me, the dogs didn’t chase her, she didn’t fly away.

It was a little odd, and not coincidentally the day after I decided to get involved in politics, formed a political action committee and filed a referendum to bring a data center development in my little small town to a ballot vote.

I joked with Jaden that the hawk was my dad, solemnly saying, “You have been denied the democratic process of voting on a matter that will drastically alter your community. Fight like hell.”

I like to imagine him pulling some invisible strings in my life, like putting a book with a lesson I need to learn on a prominent display so I notice it right away when I walk into a bookstore. Or putting a kid on my path when I work at the elementary school who talks shit to me exactly like I talked shit to him so I can have a little bit more perspective.

Throughout the last thirteen years, I’ve felt most connected to my dad on the sandy shores of the Atlantic Ocean and at overlooks on the Blue Ridge Parkway. His spirit is kept alive through storytelling, jokes, and time spent with family. Those long ass lectures about what’s right and what’s wrong have sunk in, and I live by values he taught me: to help others, volunteer my time, invest in education, read books, tell stories, throw the first water balloon, learn the history of the land I’m on and always keep a costume box in the closet.

Beautiful & heart-touching. I just have to tease you “Abe is my babe.” 😆

LikeLike

Ha! A lifetime of ridiculous things written in my diaries. Thanks for reading!

LikeLike

This was such a moving, beautifully told tribute. The stories, the humor, and the way grief and love weave together felt so real. It’s clear how deeply your dad’s spirit still shows up in your life, and thank you for sharing something so personal.

LikeLike

Thank you for these kind words 🙂 And thanks for reading!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beth,I love how you share your memories of Kenny. He was a one-of-a-kind. I miss him. ❤️

Sent from Yahoo Mail for iPhone

LikeLike

Thank you Cheri for reading. He really was one-of-a kind haha.

LikeLike