I learned something today that has forever altered the way I look at the desert.

I’ve always felt this holy sense of awe and wonder in the presence of saguaros. No picture of a saguaro has ever done them justice. I never understood how massive they are until standing underneath one, craning my neck and squinting up their spiny green flesh. Tall as trees with silly arms striking poses, reminding me of cartoon characters frozen in battle- the dancing kind.

I’ve returned to this desert for several solo trips as I nursed a broken heart back to life. Quiet company, good grieving companions. They don’t creak and sway like branches in a forest. Saguaros hold still through the day and night. Peaceful company, if you’re the kind of gal that appreciates the silent type.

The first time I ever stepped out of my car and breathed the Sonoran desert air in, I exhaled a promise: I’ll be back.

Without exploring, without knowing the creosote valleys held by volcanic mountains: misshapen, rugged peaks not at all pointy like the Cascades or Rockies. Not at all rounded like Appalachia. After only glimpsing the glowing cholla, I pledged my allegiance. Promising to learn the names of the plants that grew in this arid, hot, yet green desert.

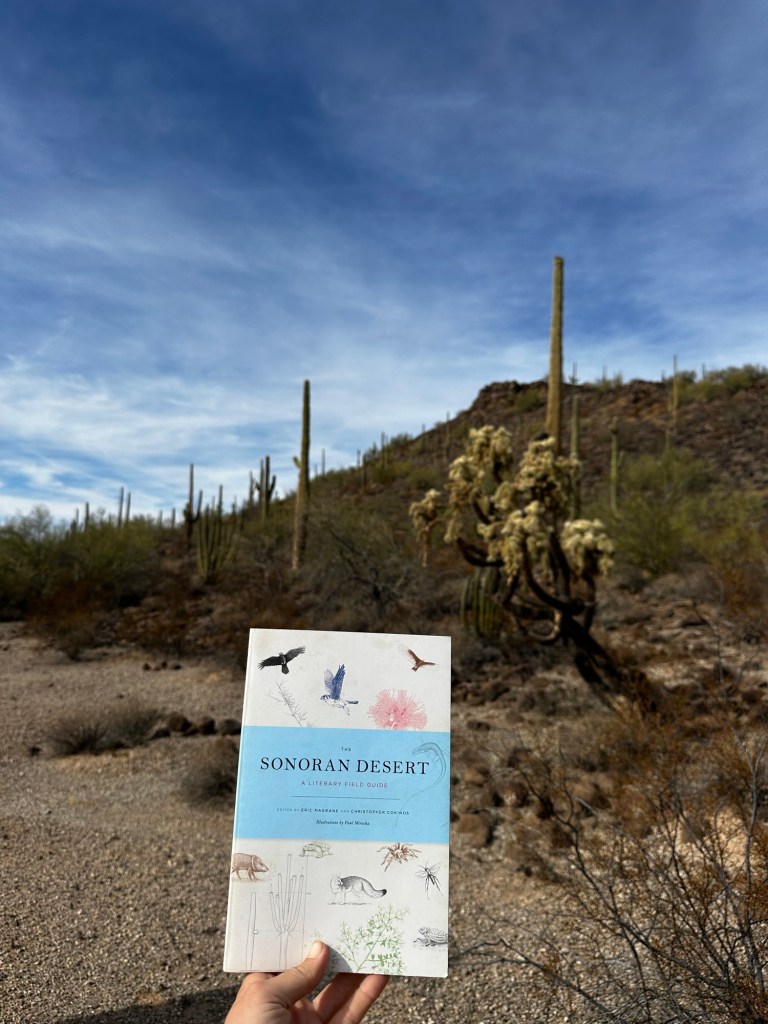

Every time I return, I fall in love with something new. Bird books, geology books, field guides, non-fiction stories of adventuring through the Sonoran fall off the passenger seat onto the floor as I drive bumpy 4×4 two tracks into the desert. Each pages teaches me to look a little closer.

Beyond the impressively tall saguaro who love the spotlight, there are many other wonders to witness. The lime green bark of a palo verde- smooth and cool to the touch. Similar to a madrone, only bright green all year round, photosynthesizing through its bark.

Sitting under the shade of an ironwood is heavenly in this scorched region. One of the heaviest trees in the world- throw it in a flood and the wood will sink rather than float. The spiny ocotillo grow brilliant red flowers at the tip like a paintbrush after winter and summer rainy seasons. Though they are covered with spikes, ocotillo are more closely related to tea and blueberries than the cactus family.

I can only read so many pages before the books fall back down to the floor of my truck and I find myself just gazing out as the desert that unfolds around me.

Time moves different here. Unhurried but never stagnant. It’s easy to lose track of the days while maintaining a pulse on the sun’s path across the sky. The pace of this place is palpable. Different than any other landscape I’ve been immersed in.

After spending a few days in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, I stopped by the Visitor Center and bought The Sonoran Desert: A Literary Field Guide by University of Arizona Press. A collection of authors write poetry and prose along with illustrated photos of the creatures and plants found in this region. That’s when I learned the secret of this place.

A clue as to why this desert captures my imagination and slows me down. Why deserts remain the setting of most pilgrimages of the soul. Why this place feels romantic and raunchy. A holy place full of wisdom. Why it moves me so deeply.

In the barren valleys grows a wiry bush with tiny reddish leaves. Sprouting from dirt, not soil, in a dusty, gray valley that stands in stark contrast to the pop of green and yellow cacti forests. An unassuming plant- the creosote is easily overlooked. Without the eye catching texture of a cactus spine you come to the desert to look for, it took several trips to fall in love with this plant.

It’s the valleys of creosote that have forever changed my perception of this place. The rows of creosote deepened my respect for an ecosystem I already adored.

The creosote is ancient. One of the longest living plants I have encountered. In the desert next door, the longest living creosote was discovered to be 11,700 years old in Joshua Tree. Can you imagine living that long? Imagine the changes you’d endure each millennia. The average life expectancy is several thousand years old.

My mouth dropped when I read that fact. I pulled up a camp chair and plopped my ass in it, now facing the creosote bushes waving between ranges of rock. In their presence I felt dwarfed, not by size but by time. What could my time camping here mean to the creosote? How fast my entire life must flash by.

No wonder this place beckons me to slow down. This green desert is operating on a different time scale than I can fully understand. Oh creosote, what else can you teach me?