I can’t help but feel like we’re living on the brink of an important historical moment. I can’t help but notice how vulnerable the western water system is. How delicate each flake of snow is, and how detrimental every degree in global temperature increase becomes. Maybe all generations feel like they’re living through history in the making.

I live on a mesa above the Glen Canyon Dam in the midst of a political war over water. Scientists call out for help as the reservoir approaches Dead Pool. The people of Page worry there won’t be any jobs left if the reservoir dries up. Marinas scratch their heads, wondering how to extend their already extended boat ramps to touch the water again.

This year the Park Service started labeling random rocks off the highway as “The New Wave” to distract tourists from an inevitable future without a lake. First time readers of the Monkey Wrench Gang still want to blow up the dam, while the Glen Canyon Institute thoughtfully details a plan to drain the lake respectfully without explosives.

Vacation folks love the lake because tubing is awesome and cliff jumping is cool. Native connections to the canyon weep, but no one listens to their cries. They have been silenced, just like the subtle current of a free flowing river has been muted.

River runners downstream of the dam just want a river to run. The children of Page cry because they want their beloved backyard lake to stay the same. Farmers in the Imperial Valley demand their Grandfather rights to the water that isn’t there, while most folks on the east coast have never heard of the Glen Canyon Dam. They think their groceries come from Kroger, totally unaware of the role the Colorado River plays in their summer salad.

Geologists laugh because the river was once an ocean, then a swamp, then an ocean again, next a river, and another swamp, then full of sand dunes, and an ocean once again before it became the damned up river we all know now. The only thing this landscape knows for sure is turbulent change.

Ordinary folk like me, born 29 years after the dam was built and grew up 2,000 miles away, have a hard time seeing the destruction that lies beneath the dark blue waters of Lake Powell.

So what if I think the lake is beautiful? Of course I love to canoe on the pristine glassy waters, breaking the stillness with a simple paddle stroke. Of course I watch with envy as houseboats float by with their rooftop decks and swirly, twirly waterslides off the back. Of course I too love jumping in and swimming the afternoon away.

This past summer, I went to the lake every day. I strapped on my fins and snorkeled above the submerged red rocks, following the fishies. Of course I love to watch the sun set over the lake, grabbing pink from the sky and putting it in the water as if they were only mirrors of each other and not separate. The lake named after a white man who claimed to discover a land that’s been here for millions of years is hauntingly beautiful.

I can admit there’s an eeriness to the lake. Seeing this much water in an arid desert certainly fills me with a sense that something isn’t quite right. It’s a bit unnatural looking if you ask me, a Virginia girl who’s used to seeing water come out of the ground everywhere.

Out here, water held in the slickrock seems like an odd choice. A place with no trees and scorching sun isn’t the best recipe for retaining water.

I suppose if I’m forced to choose a side of the argument, I have to agree with the geologists. Our little blight on the Colorado River has been called one of the greatest environmental tragedies of our time, but what does our time mean to the ancestral rocks?

Restore Glen Canyon, let the river run free! All of this I’m supposed to be aggressively shouting since I’m an outdoor loving millennial with a mostly democratic agenda. The stickers on my car try to prove that I’ve taken a side, but there isn’t anyone making stickers about being in the middle and simply wanting to observe the changes without coming to a neatly wrapped up and dramatic stance. Those stickers simply wouldn’t sell.

All the wonders of Glen Canyon I’ve only read about in books. The calm stretches of river to float, more accessible and supposedly more beautiful than the famous Grand Canyon. A fairy tale of flat water with a rich history of nomadic tribal occupation, all drowned now.

What was lost in Glen Canyon may never return. It may be ruined, history may be erased, granaries destroyed, pottery sherds buried in sediment, ancient cottonwoods deteriorated to nothing but a memory of a once lush riparian zone.

If I’ve learned anything from the harsh and beautiful desert, it’s resilience. There is no doubt in my mind that the Colorado River will run free again. Nature will have her way with this dam, she will break free…but how? And when? These are the questions I’m concerned with.

Glen Canyon may be lost just as the Western Interior Seaway will not return. This is the way of the world. Dramatic landscape changes will occur whether or not humans have anything to do with it.

Hanging on to hope that we can restore Glen Canyon exactly as it was is a death sentence. Instead, I turn my attention to wondering what will happen next? What entirely new thing might emerge?

How much time do we have left with the lake? The abomination of an environmental disaster still twists my heart with its jaw dropping, though out of place, beauty. How many years can we go on living like this- with a reservoir that’s teetering on the edge of empty? Will the politicians be so busy giving each other wet willies that they won’t notice when the waters of Lake Powell are declared dead?

If we reach Dead Pool, will all the water that’s left evaporate? Are there any Earth Firsters left that are so passionate they’d risk prison or death to blow a hole in the dam? And if they did, what would happen to all the cities downstream?

Will the conservancies and scientists get their way, with a plan to build tunnels that release water after dead pool, drain the lake and send the water to Mead? Will it snow so much in the upcoming years that the reservoir is revived for another lifetime, or will the giant mud glacier that’s floating downstream do its part to take out the dam? Clogging it or cracking it, causing the cities downstream to go into a tizzy. Will I live to see the day that the dam is no longer containing the precious water of the west?

And what might come of this little town on top of a red mesa overlooking the great dam? Will everyone up and leave because we have no water, unable to pull from a free flowing river? Will the marina jobs dry up with the tourism or could we adapt to become a river town, the first of its kind, a Glen Canyon tour company, a resupply for river runners?

What happens next is important to us humans, but not to the rocks who were once grains of sand. I feel the heavy weight of fate weighing down on western towns just as much as I feel the frivolousness of it all, measured in geologic terms.

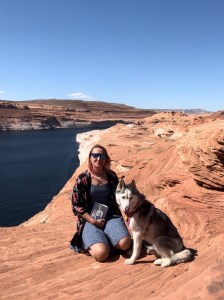

What happens next is important to me, a lover of both the lake and the river. What happens next is not up to me, a writer with a puppy and a van and a vantage point. All I can say for sure is that it feels like we are on the edge of change, on the brink of a historical moment, flirting with time.

What happens next I can’t predict, I can only wonder from the comfort of my camp chair, high atop the mesa, watching the mess of our ancestors’ decisions play out in front of me. What happens next, I’ll let you know.

Helpful Links for Further Research

- What Does Dead Pool Mean for the American West? by the Sierra Club

- Books to read about Glen Canyon

- Drain Lake Powell, Fill Mead First by the Glen Canyon Institute

- Photos and videos of the changing lake levels by the National Park Service

Get Involved with Glen Canyon

- How to Visit Glen Canyon With Respect

- Catch Fish, Get Paid by the National Park Service

- Leave No Trace

- Become a member of the Glen Canyon Conservancy- money goes to research and educational opportunities

- Sign up for newsletters to stay current with information

- Glen Canyon Institute newsletter

- Volunteer with Glen Canyon National Park Service

Love REading tHis blog? Consider Making a one-time donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Thank you kindly 🙂

Donate